To mark the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, we are showcasing an initiative aimed at the systematic inclusion of Indigenous voices in the Canadian documentary ecosystem: the digital publishing platform RavenSpace.

To that end, we spoke with Darcy Cullen, director of the University of Alberta Press and founder of the RavenSpace project, and Mavis Dixon, the platform’s business relationship manager.

The Marginalization of Indigenous Knowledge in Research

“Historically, Indigenous knowledge experts from community (without academic credentials) were not recognized as peers in the scholarly review process,” they explain.

Indeed, current modes of legitimizing scientific knowledge are tied to the colonial system, as they rely on inclusion in academic curricula and written formats, which produce documents written for the most part in colonial languages. Less institutionalized forms of knowledge creation and transmission, including some which are central to traditional knowledge, such as oral or practical modes, risk being excluded, decontextualized, reframed, or misrepresented.

These dynamics favour the perspectives and discourses of academics from outside the communities, at the expense of specialists from within those communities.

How does the RavenSpace platform counteract this institutional dynamic?

Editorial Self-Determination

RavenSpace publishes dynamic research documents produced by, with and for Indigenous communities in Canada, in collaboration with university professors, educators and editors.

Before the writing process begins, “RavenSpace invites potential authors to think about the goals of their publication and the audience.” Once the material is produced and shaped for publication, the team ensures that the peer review process is conceptualized and executed in collaboration with the authors and the other members of the concerned communities: “Community reviewers are chosen and invited to assess the work individually and together, in open conversation, guided by questions about content and presentation.”

While relying on some traditional academic standards, Ravenspace’s editorial process also breaks with certain conventions in order to fulfill its primary mission and promote the cultural sovereignty of the Indigenous people involved in the process. The team conducts two streams of peer review : academic peer review and community peer review. The latter does not seek to replicate the “blind” or anonymous review; instead, an open process of trust and assessment involves community knowledge-holders, cultural experts, and intended readers and users of the publication. This is an important step in shaping a final work that will have value and use in the community — in keeping with the goal for the fruits of Indigenous research done with and by Indigenous people be published to the benefit of Indigenous peoples.

By working with RavenSpace, members of the First Nations gain a greater degree of self-determination: “Each publication respects the choices made by the authors about how knowledge should be presented and represented based on their specific community conceptualizations of knowledge sharing practices.”

Interactive Publications and Digital Creativity

Ravenspace’s process goes far beyond the peer review process. The creative use of digital technologies allows Ravenspace to make knowledge accessible and interoperable, across multiple communities and generations.

“With media-rich interactive publications, the editorial process extends to design, thinking about the audiences and the goals of the projects, and providing advice – which we have delivered in workshops and through extended project development”, explain Cullen and Dixon.

One of the key manifestations of this digital creativity is the integration of protocols during the creation of works published by RavenSpace. These “Indigenous protocols” are both conceptual and technical. First, they set the discussion of permissions in Indigenous terms and invite frank and nuanced author-editor conversations about how content is appropriately presented and framed. For example, provenance and storytelling lineage may be prioritized and included in metadata. Or a funeral procession may not be shown in photographs but could be illustrated or described.

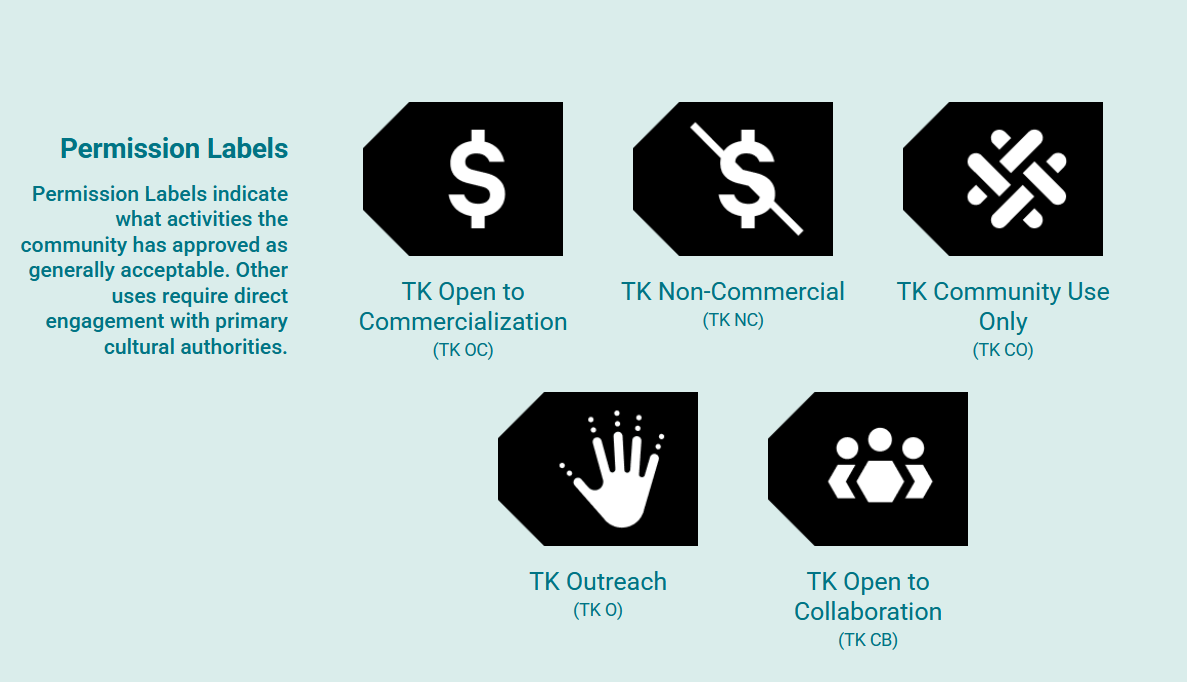

To choose the relevant protocols to put in place, the RavenSpace team relies on tools similar to Creative Commons licenses: the Traditional Knowledge Labels (TK Labels).

Developed by Local Contexts, “the TK Labels support the inclusion of local protocols for access and use to cultural heritage that is digitally circulating outside community contexts. The Labels identify and clarify community-specific rules and responsibilities regarding access and future use of traditional knowledge.”

They have helped the team to develop a specific format for the metadata. However, as Darcy Cullen and Mavis Dixon explain, “labels provide a structure for early discussion between the authors and the editor/publisher on nation-specific concepts of cultural protocols in relation to how different kinds of material ought to be held, accessed, and shared.”

An example: As I Remember It

The autobiographical work As I Remember It : Teachings (Ɂəms tɑɁɑw) from the Life of a Sliammon Elder by Elsie Paul, with Davis McKenzie (grandson of Elsie Paul), Paige Raibmon and Harmony Johnson, which includes animated sequences, vocal recordings, interactive maps, photographs and learning material, is an example of this creation process.

This digital document contains the history of the ɬaʔamɩn people (who live in the regional district of the Sunshine Coast, in British Columbia) and its most important teachings as memorized by Elsie Paul. First published as a book in a traditional format under the title Written as I Remember it: Teachings from the Life of a Sliammon Elder, the work aims to correct false, and even inappropriate, interpretations of the ɬaʔamɩn people formulated by non-Indigenous people.

As I Remember It is divided into four main thematic chapters: Territory, Colonialism, Community and Well-Being. A supplementary section lets the reader familiarize themselves with the ɬaʔamɩn language.

Before consulting the work, a message appears on screen, titled “Protocol for Respectful Guests”:

“This site is ɬaʔamɩn territory: it operates according to ɬaʔamɩn protocol. In other words, the regular rules of the Internet do not apply here. ʔəms tɑʔɑw (our teachings) are very precious, and to protect them, we invoke ɬaʔamɩn guest-host protocol to govern this site and its visitors […] As ɬaʔamɩn, as coastal people, we travel by boat. When we visit another place, we identify ourselves, describe our relationship to the host, make clear our intentions, and ask to come ashore.”

Every reader has to consent to the protocol by clicking the button “Come Ashore – I agree,” guaranteeing a continuity between the reading experience and the traditional practices from the author’s culture.

While exploring the work, the reader encounters several TK Labels. For example, the ʔəms naʔ Label (shown here), which refers to sensitivity to cultural differences, is shown when the author wants to state that the teachings, laws and practices mentioned are held and managed collectively by the ɬaʔamɩn people.

What’s Next

The RavenSpace initiative is part of a series of declarations, such as the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA), which has, as one of its objectives, the preservation of the cultures of Indigenous peoples in a way that is respectful of the practices of each nation.

More specifically, as Darcy Cullen and Mavis Dixon explain it, “we are working to elevate the appreciation of publishing’s positive role in advancing Indigenous self-determination, governance and recognition of treaties, rights and titles; health; economic and social rights.”

To learn more about a similar project, working to ensure the self-determination of First Nations in Canada in the documentary sector, we invite you to consult our previous blog post about the project to revise the Répertoire de vedettes-matière of the Université Laval.